Related Content:

Caught in a Vicious Cycle: Obstacles and Opportunities for Trust and Safety Teams in the Games Industry

Executive Summary

How can the games industry reduce disruptive behavior and harmful conduct in online games?

These phenomena have become normalized in online games, and it is not only players but also industry employees who suffer.

Since 2019, ADL has conducted an annual survey of hate, harassment, and extremism in online multiplayer games. Our 2022 survey shows that hate continues unabated. More than four out of five adults (86%) ages 18-45 experienced harassment. In addition, more than three out of five young people ages 10-17 experienced harassment.

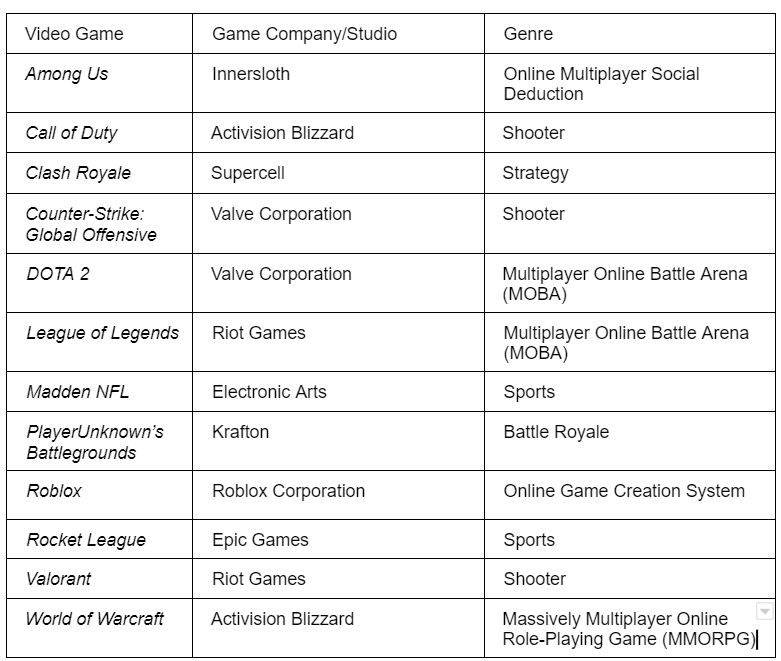

For this report, however, ADL decided to focus not on users’ experiences but on the challenges faced by trust and safety employees in the games industry when it comes to moderating hate and harassment. ADL wanted to determine whether game companies prioritize content policy enforcement and whether they give staff adequate support. Building on our previous work, the ADL Center for Technology & Society analyzed the policy guidelines of 12 games and interviewed a number of trust and safety experts in the games and technology industries.

Our recommendations are:

- Assign more resources to understaffed and overwhelmed trust and safety teams in game companies. Teams are bogged down by institutional challenges, explaining the value of content moderation to skeptical executives and securing bigger budgets to hire more staff and expand their work.

- Make content moderation a priority in the creation and design of a game. Trust and safety experts say content moderation should be central from a game’s conception to its discontinuation.

- Focus content moderation on the toxic 1%. Networks, not individuals, spread toxicity. Game companies should identify clusters of users who disproportionately exhibit bad behavior instead of trying to catch and punish every rule-breaking individual.

- Build community resilience. Positive content moderation tools work. Use social engineering strategies such as endorsement systems to incentivize positive play.

- Use player reform strategies. Most players respond better to warnings than punitive measures.

- Provide consistent feedback. When a player sends a report, send an automated thank you message. When a determination is made, tell the reporting player what action was taken. This not only shows players that the team is listening, but it also models positive behavior.

- Avoid jargon and legalese in policy guidelines. These documents should be concise and easy for players to read. Every game should have a Code of Conduct and Terms of Service.

The games industry has reached an inflection point, with games acting as powerful vectors of harassment and radicalization. Regardless of age, users will likely experience abuse when they play.

Games function as entertainment and sources of community for millions of people. If the industry continues to deprioritize content moderation, it will send a clear message to users, especially marginalized groups, that games are not safe, welcoming spaces for all. We hope this report serves as constructive criticism for an industry that figures prominently in the American social and cultural landscape.

“We Can’t Control User Action”

The value of trust and safety may be best illustrated by what happened after Twitter dissolved its Trust and Safety Council and made deep cuts to its trust and safety team. ADL found a 61% increase in antisemitic content on Twitter two weeks after Tesla CEO Elon Musk bought the company. Twitter lost half of its top 100 advertisers, with companies citing concerns about their brands being associated with inflammatory content on the platform.

The work of trust and safety teams is complex; they wrestle with many thorny issues: free speech, democracy, and privacy, among others. With respect to the games industry, teams do not have the resources they need to address toxicity. Games have exploded in popularity, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic, but companies’ trust and safety operations remain bare-bones. Moderation was once the simple process of preventing players from using offensive words. As games continue to evolve, overburdened teams must also moderate text, audio, and even custom game modes.

Recently, a user-created mode that simulates sexual assault appeared as one of the most popular modes in Overwatch 2. The mode enabled players to impregnate female characters in the game by knocking them down and forcing themselves on top of them. At the top of the screen, as reported by the publication PC Gamer, the mode said “raping…” until the female character was marked as “pregnant.” Players could then wait for the baby to be born as the denouement of this appalling chain of events.

What the example of Overwatch 2 illustrates, aside from the blatant misogyny that continues to plague the games industry, is that current approaches to content moderation are ill-equipped to deal with the forms of harmful conduct players face. In the same article about the sexual-assault simulator found in Overwatch 2, PC Gamer reported, “It doesn't appear that Blizzard’s moderation tools automatically filter out those words from the title or description. You can report modes from their information pages for ‘abusive custom game text,’ but Blizzard doesn’t let you type in an explanation like you can when reporting players.”

As of the article’s publication in January 2023, Activision Blizzard has not shared a plan for how it would prevent the simulator from reappearing in the game.

Even with supposed guardrails in place, violative content still reaches users. Roblox, for instance, filters games according to age, with those tagged as “All Ages” deemed appropriate for children as young as five. Yet as one concerned parent whose children were Roblox users discovered, the filtering system exposed young players to disturbing content. It was easy for the parent, a games industry veteran, to circumvent Roblox’s moderation.

“I initially started this experiment to talk about the aggressive use of microtransactions and pay-to-win mechanics that condition kids to the games-as-a-service model,” the parent said. “I didn’t expect to find weird pedo stuff and bathroom voyeur games and suicidal idealization.”

After the parent shared her findings, the publication NME reported that a Roblox Corporation employee allegedly said, “Well, we can’t control user action, we can only act on reports.”

Unwittingly, the employee revealed much about the industry’s approach to content moderation—it is too reliant on being reactive rather than proactive. Removing harmful content after thousands of children have seen it, only for that content to sprout again, hardly indicates success.

It is time for game companies to rethink their content moderation strategies.

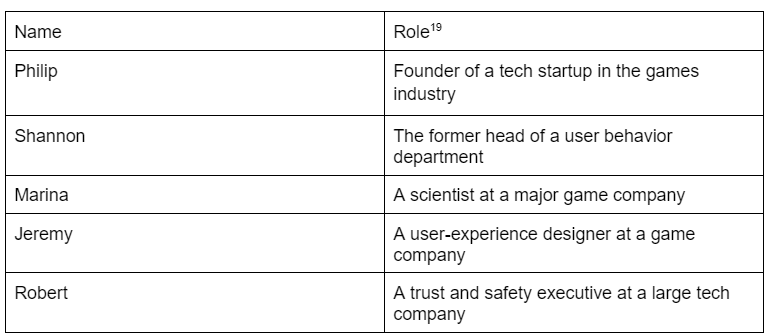

ADL analyzed the landscape of content moderation in the games industry. We analyzed the content moderation policies of 12 games and interviewed leading trust and safety experts in games and technology. To protect their identities, they were assigned the following pseudonyms:

- Philip, the founder of a tech startup in the games industry

- Jeremy, a user-experience designer at a game company

- Shannon, the former head of a user-behavior department

- Marina, a researcher at a major game company

- Robert, a trust and safety executive at a large tech company

We sought to answer the following research questions:

- What do trust and safety experts identify as the main obstacles to effective content moderation in online games?

- Which strategies support robust content moderation?

- What are examples of clear, comprehensive policy guidelines?

- What are the best practices around cultivating positive play, what constitutes active moderation, and how can companies provide better player support?

Game companies cannot control users’ actions, but they can influence their behavior and experience to a large degree. They can even decide which types of user behavior are prohibited and welcome in their games. Companies can create more-positive environments by not solely relying on punitive measures such as bans, which have limited efficacy. We hope this report expands the industry’s understanding of content moderation and the ways it can improve.

Results

Obstacles to Content Moderation

Caught in a Vicious Cycle

In our interviews,[1] we asked about current content moderation strategies and the barriers to implementing them.

Trust and safety teams struggle with small staffs, small budgets, and unmanageable workloads. A common complaint expressed by the experts we interviewed was about industry executives’ lack of understanding of how much work content moderation entails.

Robert, a trust and safety executive at a large tech company, recalls that before his employer acquired a competitor, it had only two community managers to review appeals and resolve disputes, in addition to an external vendor. After the acquisition, the company still devoted few resources toward trust and safety.

“Even with the $4 billion a year that [the company] makes,” Robert says, “the amount that they put into trust and safety is very close to nonexistent given the size of the company.”

"If industry executives are not convinced that content moderation can impact company revenue, they will not invest in it," Philip, the founder of a tech startup in the games industry, says, "or at best they'll view it as a cost center that they should spend the least they can on to check the box."

“[Trust and safety teams] need to tell that story to executives: That a dollar spent in trust and safety generates X dollars out the other side,” Philip says. “But it’s only recently that innovators in the games industry have started to measure the revenue and retention impacts from content moderation. It’s easily measured with simple A/B tests of moderated versus non-moderated experiences, but it hasn’t been considered part of the game’s user experience until now – and only by a few game studios.”

"Executives," Philip adds, "have a poor grasp of content moderation." He has met with many industry executives who say they want “more effective moderation,” meaning the removal of specific hate speech phrases and expletives. This is a limited view of the complexity involved in content moderation. Experts such as ADL Belfer Fellow Libby Hemphill, a computational scientist at the University of Michigan, warn that a focus on profanity ignores larger problems presented by the online hate ecosystem.

“When content moderation is too reliant on detecting profanity, it ignores how hate speech targets people who have been historically discriminated against,” Hemphill wrote. “Content moderation overlooks the underlying purpose of hate speech—to punish, humiliate and control marginalized groups.”

Another challenge cited by trust and safety experts is that a single game company may have multiple games of different genres. League of Legends is a multiplayer strategy game that requires different moderation strategies than the shooter Valorant, for instance.

Jeremy, a user-experience designer at a game company, says, “Each game needs to identify the types of disruption that they expect to see in their games.” For example, the ways in which disruptive behavior appears in a shooter game with voice chat may be different and require different resources than the ways in which such behavior manifests in a sports game with text and voice chat.

Even trust and safety teams buoyed by strong support from executives have difficulty figuring out the content moderation needs of varied games.

Marina, a researcher at a major game company, notes that although her team is hiring more associates, the company’s support remains insufficient.

She says, “We have so many games, and they all have different priorities and resourcing needs right now.”

Marina’s comment raises questions. Broadly, how do companies direct the focus of their trust and safety teams? Do the most popular games receive the most attention? Or do the games with the most offending players? Does the level of content moderation depend on the type of game, i.e., a card game or a battle royale?

Robert argues that the problem comes from the companies’ lack of willpower rather than a lack of data.

“Anyone can put up rules on their website, but I think where the rules really start mattering is when people start leaving because of these things,” Robert says. “Gaming has historically not kept a good understanding of churn, because they don’t need to.”

Trust and safety teams are caught in a vicious cycle. They are understaffed and underfunded because executives do not believe the quality of content moderation affects revenue, which then means teams do not have the money to conduct research to generate data on the value of content moderation, and thus teams have no data to demonstrate their work’s importance to executives.

Inconsistent Priorities

Trust and safety experts say that if a game is not developed with content moderation strategies from the start, it is tough to solve subsequent problems. Game companies need a consistent philosophy on content moderation that is clear to all departments. Content moderation should not be the sole responsibility of trust and safety teams.

For example, engineering departments must build in-game warnings and alerts. If those systems are not developed early in a game’s life cycle, they will not be available later.

“One of the reasons you end up not having the capacity for moderation and other necessary tools is because it’s not something that’s at the forefront of many developers’ minds,” Shannon, the former head of a user-behavior department, says. “So you launch the game, you have a problem, and suddenly you’re scrambling to try to figure out what you can do about this.”

Epic’s struggles in moderating content on Fortnite is an example of the danger of not developing games with content moderation at their core. According to ADL’s 2022 annual survey of online hate and harassment in games, 74% of adults over 18 and 66% of young people ages 10-17 experienced harassment while playing Fortnite. It is also one of the games in which players most often encounter extremist white-supremacist ideologies.

Fortnite has only voice chat, which one interviewee identified as a significant problem in moderating content. As ADL has noted, the tools available to moderate audio content are less developed than those used to detect text. Audio content is often transcribed into text via automated transcription software. Then, the transcribed text runs through more established text-based automated content moderation tools.

The problem with this method is that automated tools are unable to process the nuances of

oral speech: volume, pitch, or emphasis. When audio recordings are transcribed, these nuances are flattened and often contain only the words spoken, potentially leading to mistakes in content moderation systems trained to evaluate textual content as the entirety of a comment’s intended meaning. Furthermore, audio takes up more storage space than text—and storage costs money. More recently, some voice-native moderation solutions have made it a core business priority to acknowledge and address these issues.

Shannon says content moderation should be central to a game’s development “from ideation all the way through to launch through to sunsetting.” But if executives are not telling engineering and development teams to factor in content moderation from the beginning, companies will be unprepared to address harassment when it occurs.

Content Moderation Strategies: What Works?

The trust and safety experts we spoke to agree that content moderation needs to evolve. We identified five strategies that move away from administering punishments and toward building positive, prosocial game spaces.

1. Focus Content Moderation on the Toxic 1%

Trust and safety experts advise shifting away from attempts to focus moderation on individuals because this approach creates a game of whack-a-mole. Previously, trust and safety teams paid more attention to users who consistently flouted community rules, trolled other gamers, or spread hate.

Experts now suggest that companies direct more of their punitive measures to curbing the behavior of the few players who are disproportionately and persistently toxic. To better moderate community behavior, trust and safety experts say, it is important to understand that most players are not trying to break the rules.

Jeremy estimates that only about 1% of players are “really awful,” but they have an outsize impact because they play frequently. Individually focused moderation results in treating the 99% of players who make occasional mistakes the same as players with malicious intent instead of creating a separate category for repeat offenders.

“Once content moderation teams identify these players,” Philip says, “they can make targeted efforts. Our data shows there is typically a tiny minority of users – typically less than 3% – who produce between 30% to 60% of toxic content across all types of platforms. Removing these bad actors can immediately remove a lot of hateful content in a game. For the vast majority of players, though nudges, warnings, and other forms of group behavioral modification, rather than suspensions or bans, do a far better job of stopping toxic behavior. The goal is to guide people toward social norms they may not be aware of. Most people, once they know what’s acceptable, are fine adapting to it.”

The consequence of toxicity is that it can turn off new players. There is a “600% drop-off rate” for new players who encounter a toxic community, Philip says, adding that new players are then “more likely to say, ‘They’re not my people; this isn’t my tribe. I'll see you later. I'm out.’”

“Given how much it costs gaming companies to attract first-time users, losing them because of a hateful comment from another player is expensive,” Philip added.

Shannon expressed similar thoughts: "If we ban that account, it's just a revolving door. They [toxic players] just hop right back on and create another account. A lot of times, the new players are the ones that then bounce. And so the ones that have been around longer are sort of hardened.”

Banning a player for using a slur does little to prevent bad behavior. As Shannon says, experienced players can change their accounts and return to the game. New users may be banned, not realizing their behavior is unacceptable, because they did not read the Code of Conduct. These users may retreat from the game permanently. Assuming a company’s goal is to maximize revenue, banning can be self-defeating, Jeremy warns.

“If you just ban a player, you’re probably gonna lose that business forever, right?”

The punishments in these spaces are meted out haphazardly: While some users engage in violative behavior without consequences, others are banned permanently for small infractions.

An approach to content moderation that is too reliant on individuals using obvious hate speech or foul language fails to distinguish between networks of repeat offenders who intentionally create hostile environments and users who unwittingly break rules. It hurts users, and it hurts revenue.

2. Build Community Resilience

What happens when bad actors spread toxicity outside of a specific game’s community? Toxic players can also affect a game’s Discord server, subreddit, and other platforms, Philip says.

“You can literally draw a line between the people that [toxic players] interact with and the users that were exposed to a certain community or a certain game where they’re in the waiting room. You see misogyny creeping up over time, and then it holds flat. You start to see hate speech coincide and go up. And then, eventually, the triggers start to go off for grooming.”

To offset the threat of toxicity spreading, game companies build resilience, or encourage communities to develop and cement social bonds with the goal of resisting bad actors who seek to change a game’s climate. Shannon defines resilience as the development of “personal accountability” for community members who break the rules and the “development of better skills for emotional regulation for all players.”

Resilient communities are not only more positive but also make players more open to reform. Jeremy found that 85% of players of a popular shooter game were responsive to behavioral modification attempts, but with positive reinforcement such as praise from teammates, the figure rises to over 90%.

An increase of five percentage points may not seem significant, yet consider that positive reinforcement influences the remaining 15% of players, who normally would not respond to any attempts at reform. Jeremy points to community resilience as a key part of this change. Positive, resilient communities, he says, make “fertile ground for all the other stuff,” such as player reform and behavioral modification.

Shannon helped implement a reward system in a leading MOBA (multiplayer online battle area) game in which players give kudos to others at the end of a match. The more kudos a player receives, the higher their reward level, and the higher their reward level, the more perks they earn. Perks are objects that can help players progress in a game. This reward system, Shannon says, is “our way of injecting resilience into the narrative of the players” by compelling players to hold each other accountable and enforce good behavior, thereby strengthening the community.

Marina worked on a similar reward system in a popular shooter game. Players can give rewards, which function as compliments, to others after matches, such as “good teammate” for friendly players. This reward system gifts players with in-game items as incentives. Marina said that adding the reward system resulted in “a roughly 40% reduction in disruptive chat that has remained reduced throughout the whole time.”

When game companies switch from punishing the behavior of individual bad actors to modifying the behavior of a game’s community, they can achieve lasting, positive change, Jeremy says.

“Generally, companies have been focusing on the person, trying to change the world one person at a time, right? They should be looking at the other part of the equation, which is the environment part of it. Because if you change the environment, you change the behavior.”

3. Use Player Reform Strategies

While building resilience is an effective content moderation strategy, rule-breaking still must be addressed. Resilience and managing group behavior are meant to manage the majority of players, but the few who are consistent rule-breakers warrant punitive measures such as bans or suspensions.

Solely relying on punitive measures is inadequate. When a player is banned, they either leave the game (especially if they are a new player) or create a new account and return to offending. Despite their shortcomings, punishments are necessary as a last resort.

Before such measures are taken, game companies can try player reform strategies, which are deployed before punitive measures like banning to warn players that their actions will have consequences. The advantage of player reform is to compel gamers to become, Philip says, “cheerleaders and champions” of new players, leading to better retention rates and greater community resilience.

“No one wants to ban anyone,” Philip says. “They want them there to be a contributing, good steward of that community.”

In-game warnings are a player reform strategy. The popular shooter game that Marina worked on has a warning that appears when the moderation system detects a player changing their behavior “for the worse, but before they’ve reached a threshold that we would penalize them.” For a user who has been reported multiple times for transgressions like griefing[2], leaving the game early or other aggravating conduct, her team found that the in-game warnings they implemented were successful in reforming players.

“We have seen a significant portion of players who receive [an in-game warning] change their behavior and not go on to be penalized,” Marina says.

Other game companies also have in-game warning systems. Robert, who worked on a popular shooter game, describes that company’s in-game warning system as being similar to the one in the shooter game being worked on by Marina’s team.

“They’ve set up volume metrics based on triggers where if five people report you within the span of, you know, 10 minutes, and it’s five unique people, then a warning happens on your platform,” Robert says.

However, the developer is skeptical of this approach because in-game warnings are not paired with player reform.

“[The game company] has a list of things that you cannot put in your username. And the way of enforcing that list is that they force you to change your username. And that is about the extent of it.”

Even though this shooter game implements in-game warnings, the company only logs the event. They do not provide further resiliency measures, like the aforementioned shooter’s reward system, or make other attempts to reform the player. This could be one reason Marina’s team’s shooter has seen some success with regard to the implementation of in-game warnings, while Robert’s team’s shooter game has not seen the same success.

Poor implementation of in-game warnings serves as a reminder that these strategies are not enough. To carry out these strategies effectively, punitive measures must be paired with community resilience. For example, a player may give kudos to a good teammate, a form of community building, but when a player needs to be corrected, an in-game warning can serve as a less punitive corrective measure. Trust and safety teams can use punishment, such as a ban, as a last resort for the most obstinate players.

4. Providing Consistent Feedback

Player toxicity is not the only problem trust and safety teams face. If games are not moderated well or mistakes are made, users revolt. When World of Warcraft’s (WOW) moderation system mistakenly banned Asmongold, a popular WOW streamer with millions of followers, from the game for a policy violation, he was so incensed he stopped playing. At the same time, if moderation is not robust, games could lose current players and put off new ones. Research shows that the social environment surrounding a game is related to player churn. If games are not welcoming spaces where users can play with their friends and form new relationships, player churn can worsen.

Often, players do not know why they have received a warning or ban, even with in-game warnings, which players often skim or ignore. In-game warnings appear only after repeated reports of a particular player. Players often play multiple rounds of a game in a row and often do not remember the exact action that caused them to receive a negative report. New players are especially susceptible to this, since they are not fully acclimated to the community, so trust and safety teams must create systems to offer players feedback.

Feedback means not only educating players about what they did wrong but also consistently communicating with them. In her interview, Marina remarked that feedback is integral to systems of reward and punishment because these systems are tied to reports from players. If players do not feel their reports matter, they will not report abuse, directly affecting whether in-game warnings and other tools are used. Her team added messages that appear after a player has been punished as a result of being reported.

“We thank everyone who reported that person to get people using the reporting system more, so that we get more of this data coming in and we can go through some more of those early interventions,” Marina says.

These messages not only alert players that the report system is working but also model positive behavior.

Consistent feedback is crucial for a content moderation strategy’s success. It serves to inform the moderation infrastructure and educate players on what constitutes poor conduct.

“Feedback for the players is just letting them know, ‘Hey, this is not normal behavior, or this is not considered appropriate behavior,’” Shannon says.

When systems of feedback are missing, content moderation tools are less effective. For example, Robert said that in the popular shooter game he worked on, users select a reporting option from a dropdown menu, but there is no way for the company to follow up with users after they submit a report, and no feedback is given to players accused of misconduct besides an in-game warning if they are reported several times.

This reporting system provides the company with little information about what kind of harassment occurs within the game. Robert says:

“It's impossible to tell what actually happened. Did they harass you because they were teabagging[3] you? Unclear. Did they harass you? Because they were in a party and they got on voice and they said something really terrible to you? [The game company] has no way of determining whether that isn’t true."

Consistent feedback benefits game companies, too. It enables trust and safety teams to measure recidivism, or the rate at which players will reoffend. Recidivism is notoriously hard to measure. If players are banned, they can create a new account, making them hard to track. If a company knows it has warned a player about their behavior, and the player has not received another warning in months, that is valuable data on how well different moderation approaches work.

In the same way that in-game warnings do not work as well without group behavioral modification, behavioral modification and resiliency measures do not work without feedback. Consistent feedback is an important and necessary part of player moderation, says Philip.

“It's important for people to get that kind of feedback. It’s how we grow. It’s how we learn.”

5. Avoid Jargon and Legalese in Policy Guidelines

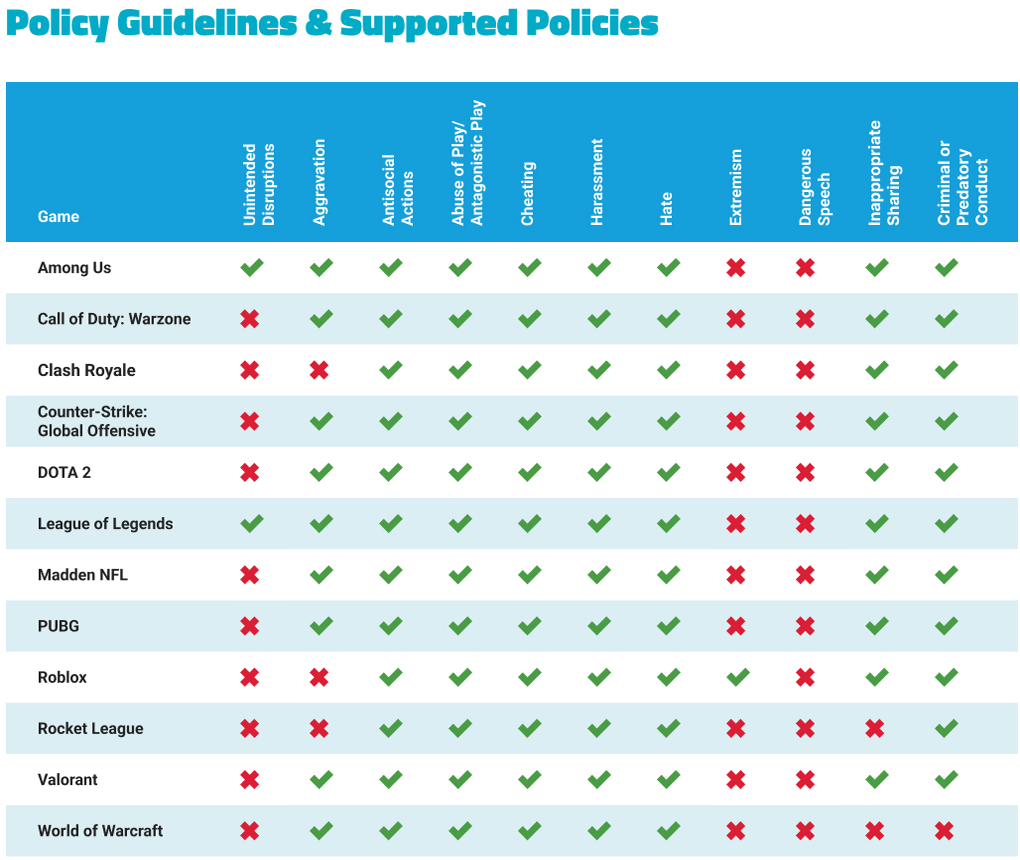

We found that game companies inconsistently define types of bad behavior and do not explain their policies well for users.

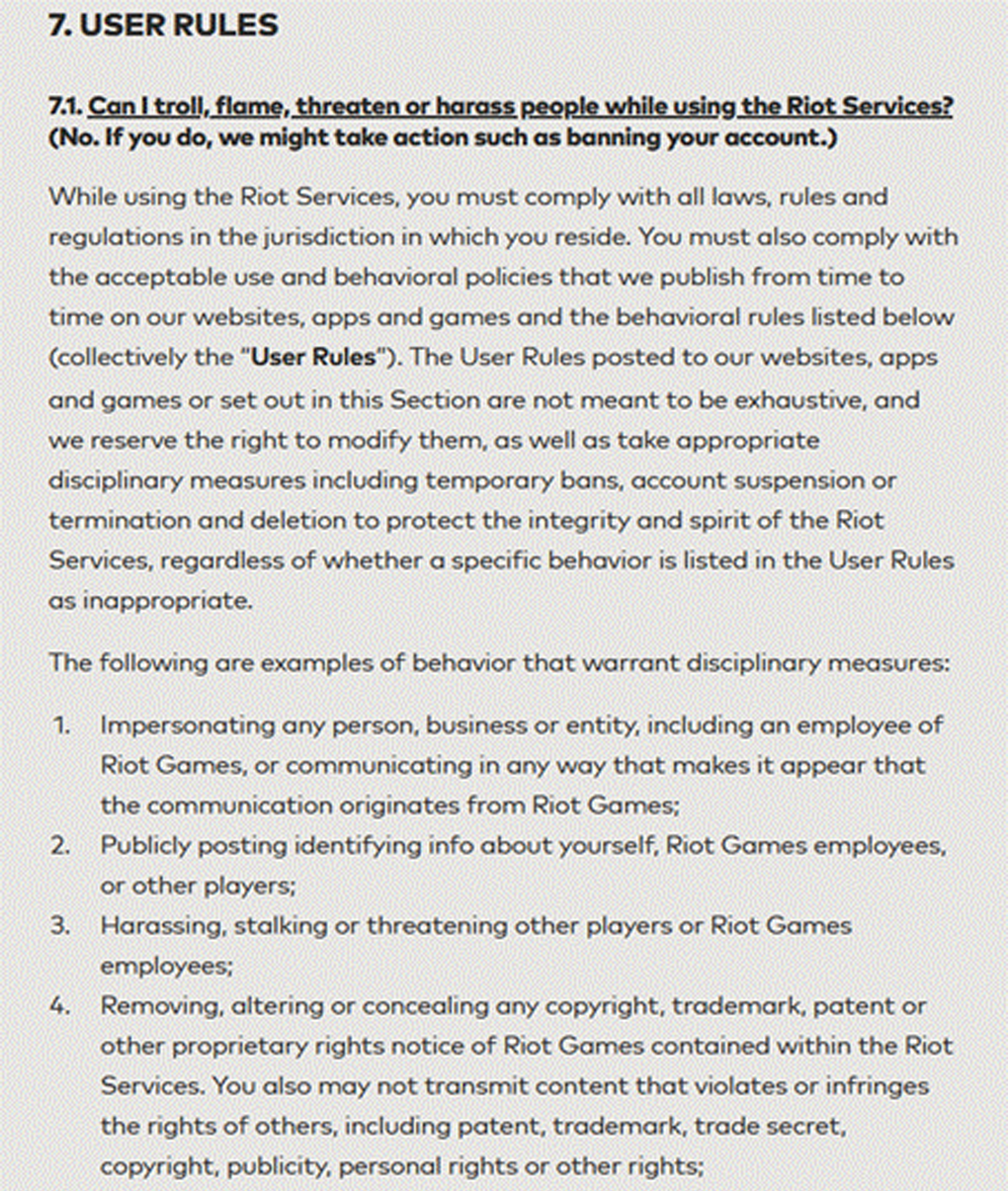

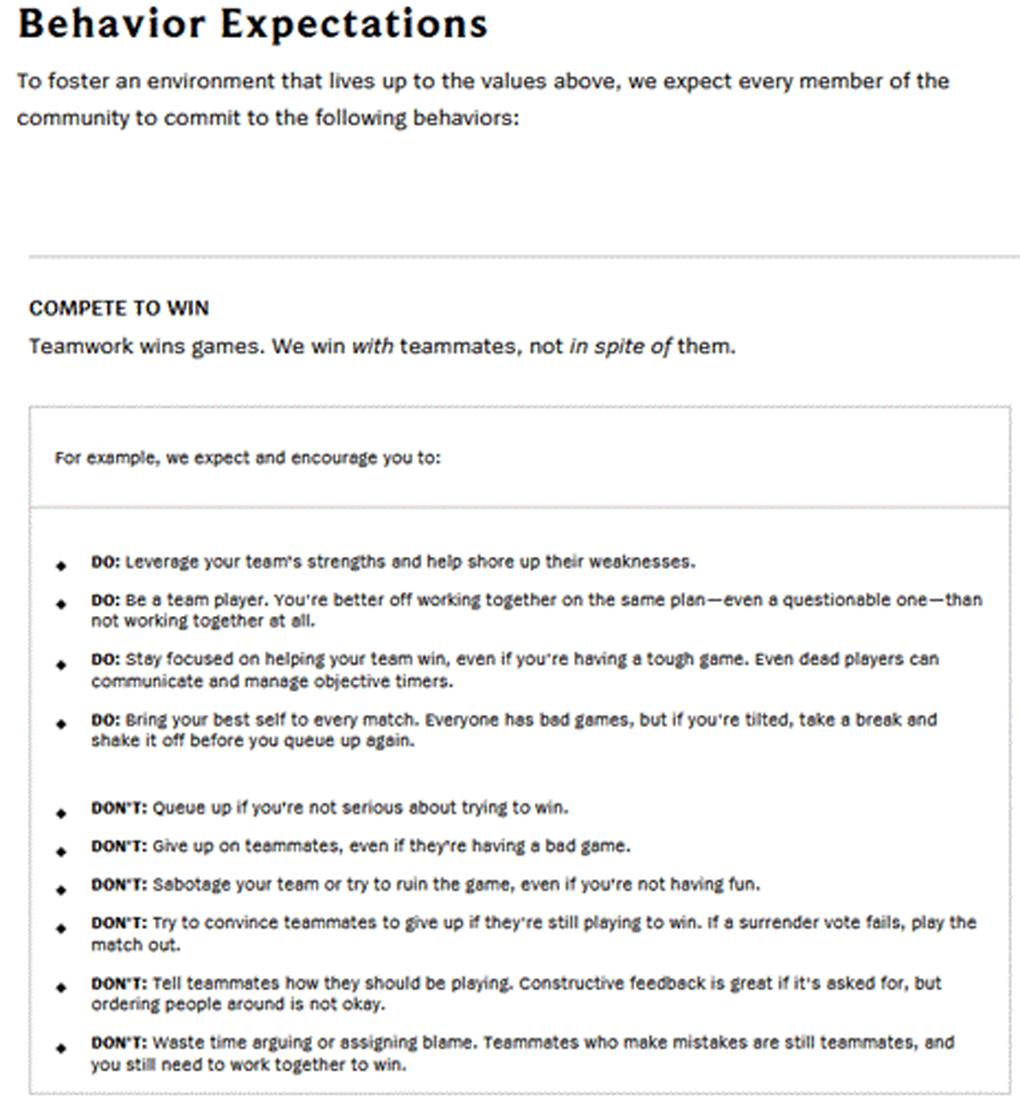

Every game company we reviewed had policy guidelines around player conduct. These policy guidelines are separated into two categories: Codes of Conduct and Terms of Use (also called Terms of Service or End User Agreements[4]). The latter is a legal contract, while the former is not. All games have Terms of Use contracts, but not all have Codes of Conduct.

ADL analyzed each game’s Codes of Conduct, and if it did not have one, we looked at other policies such as Terms of Use, Community Standards, or Online Conduct Rules.

Policies were then organized under 11 categories based on ADL’s “Disruption and Harms in Online Gaming Framework,” which was developed in 2020 at the behest of the games industry to establish clear, consistent definitions of bad behaviors that can function as a shared lexicon. The Framework was prompted by ADL finding inconsistent definitions of bad behaviors within games at the same company, let alone when comparing different companies.

In our analysis, we saw scant adoption of the Framework’s guidance; companies do not define or distinguish these categories clearly. Each game had different types of disruptive behavior it did or did not ban. League of Legends and Valorant, despite both being developed by Riot Games, have slightly different prohibited behaviors. Every game should have language banning every category of disruptive behavior. Although many categories of behavior overlap, that does not mean they are the same. For example, not all harassment is hate-based. A player could harass another player to annoy them, not because of a target’s identity characteristics. Every policy should be clear and distinct in describing the specific forms of behavior that are banned.

The least likely categories to be included were dangerous speech[5] (zero games), extremism[6] (one game), and unintended disruptions[7] (two games). In contrast, every game had some language in its Codes of Conduct banning or at least limiting antisocial actions[8], abuse of play[9], cheating[10], harassment[11], and hate.[12]

Valve has not published Codes of Conduct for DOTA 2 or Counter-Strike: Global Offensive. Instead, it uses the online conduct rules and subscriber agreement from Steam, its distribution service and storefront. Steam’s online conduct rules states that Steam subscribers will not “Defame, abuse, harass, stalk, threaten or otherwise violate the legal rights (such as rights of privacy and publicity) of others.” [13] This sentence could be interpreted to cover the “dangerous speech” category, as it forbids “defaming” others. However, it does not explicitly ban this action as speech (chat, voice calls, etc.) and so was not included in our tally for dangerous speech.

A more fundamental problem underlines content moderation policies: Few users can penetrate their jargon. We found policies named Codes of Conduct rather than Terms of Use are more likely to be read because they are easier to understand, lacking the dense legalese of Terms of Use contracts.

Riot Games' Terms of Service

League of Legends' Code of Conduct

Interviewees emphasized explicit rules as necessary for players to understand what they did wrong and why they were punished. Marina states that “behavioral contracts” are displayed before players start any of the games she helped develop.

She says, “[Players] really don't understand why they’re penalized. Part of the hope with their behavioral contract is that if there are gaps in what players think is okay but we don’t, [the gaps] can be closed.”

Players will be better able to understand what is expected of them when each rule is delineated and separated in a behavioral contract, Codes of Conduct, or similar documents. Players can then easily refer back to the document and see why they were punished.

Codes of Conduct need to be written precisely but must also be relevant to problems that can arise in a game. Shannon reported having difficulty with players “breaking the meta” in the popular MOBA she worked on. The “meta” is the optimal gameplay or strategy a player uses. Because this game is over a decade old, players have settled into a routine of how to play (the interviewee estimates that about 99% of games are played in the meta). However, when a new player does not know the “meta,” they often face abuse even though they do not intend to harm or annoy people.

Non-meta players, the developer says, “were sometimes the most reported people in the ecosystem because people thought they were just being jerks. So you would have these people that would just get dogpiled by people harassing them, and then that could sometimes escalate to really inappropriate things.”

Some games have this abuse covered in their Codes of Conduct. For example, League of Legends’ Code of Conduct states:

“Showing up to win doesn’t mean restricting yourself to playing what’s meta. Trying something new is a valid way to play—as long as you're still supporting your team and making an effort to win. Keep in mind this extends to your teammates: Even if you disagree with their playstyle, give them a chance and focus on winning as a team.” [14]

But League of Legends is only one of two games (the other is Among Us) that provides guidance about “unintended disruptions” in its Code of Conduct. DOTA 2 does not provide this language, even though it also has a “meta.”

Although policies labeled Codes of Conduct are more likely to be read by players, it is not guaranteed they will; most players skim or skip them. To address this problem, League of Legends requires players to agree to an abbreviated form of its Code of Conduct by clicking the “I’m in” button. Players who decline are not permitted to queue for matches until they agree. Nevertheless, there is still no guarantee they will follow the rules, and more measures must be taken after this stage to cultivate positive behavior.

[2] Content that dehumanizes or portrays others as impure, especially content that makes violence a necessary method of preserving one’s identity.

[3] Support or recruitment to the radical wings of broader movements, or terrorism.

[4] Miscommunication in language or cultural barriers, skill mismatch, and playing against the “meta.”

[5] Frequent negative comments, hostile responses, and general hostility.

[6] Trolling, sabotaging, rage quitting, and griefing.

[7] Bots, automated farming, loot and/or item finders, and manipulating game stats/settings.

[8] Mobbing/group bullying, offline harassment, identity-based harassment, and instructing others to self-harm.

[9] Intimidation, ridicule, and insults related to identity.

[11] For more information on our interviews and general research methodology, please see the Appendix.

[12] Griefing is defined as deliberately harassing or annoying other players in an online multiplayer game.

[13] When a character in a game places themselves on top of another character.

[14] Terms of Use, Terms of Service, and End User Agreement are used interchangeably. We saw no significant difference between these documents.

Conclusion

Community behavioral modification through positive play works best for game platforms. Punitive measures show limited success and have the potential to turn off users.

However, these strategies cannot be done piecemeal. All five of the strategies we identified must be used in conjunction with one another. They cannot work independently, because each strategy builds upon the other. For example, without feedback from players, there is difficulty in gathering data on recidivism. Without data on recidivism, there is no way to measure whether the other strategies are working effectively.

In addition, companies should consider internal obstacles to content moderation, such as skepticism from executives. Community behavioral modification works, but without money to fund research and hire more staff, trust and safety teams cannot implement these measures. They need executives to prioritize trust and safety early in the game development process so that content moderation is treated as a priority, not an afterthought.

Recommendations from ADL Center for Technology & Society

Provide more resources to trust and safety teams. Content moderation teams at game companies are often strapped for money and staff. Within the same company, teams may be responsible for monitoring multiple games, each with many moderation needs. Providing teams with more funding and personnel can lessen their strain and provide them with the time to implement new content moderation strategies.

Consistently apply company-wide policy guidelines. Ensure every department in your company has a thorough understanding of your content policies. User trust and safety should concern all employees in a game company, not only content moderators.

Factor content moderation into the development and design of your games. Content moderation decisions should be decided from the ideation point of game design. If content moderation is not considered, it is difficult to implement moderation strategies in games later. That said, it is possible for games that have already been released to implement these recommendations for important trust and safety features, but it may require significant additional resources after release.

Collect content moderation data. Not collecting data on content moderation creates a catch-22. For company executives to take content moderation seriously, data needs to be collected. But if data is not gathered, then trust and safety teams cannot provide a justification to invest in content moderation. There is plenty of data on the effect of content moderation strategies in games. Companies need to invest in researchers to gather this data and analyze it to show that content moderation strategies not only work but also create quantifiable results.

Avoid jargon and legalese. Terms of Service function as legal contracts and are dense with jargon that is impenetrable to most users. Codes of Conduct, on the other hand, are more user-friendly and meant to outline the kinds of behaviors that are forbidden in a game. When companies label their policy guidelines as “Codes of Conduct,” they are more likely to be read than Terms of Service. They should avoid vague or technical language within Codes of Conduct and give examples of policy violations whenever possible. If a policy states, “Players will not harass each other,” add an example of harassment.

Make policy guidelines relevant to your game. A game with a “meta” style of gameplay, for example, should include language that bans harassment for “breaking the meta.”

Identify the group dynamics in your game. It is likely that only 1% of your players are responsible for the majority of hate and harassment in your game. Use data to identify these players.

Promote community resilience. Most players do not want to break your rules. Use social engineering strategies such as endorsement systems to incentivize positive play.

Warn players before escalating punishments. Most players respond well to warnings instead of punitive measures such as bans or suspensions.

Provide consistent feedback to the community. When a player sends a report, send an automated thank you message. When a determination is made, tell the reporting player what action was taken. This not only shows players that the team is listening but also models positive behavior.

Appendix: Research Design and Methodology

The research is separated into two categories: game policy data and interview data.

Research Sample

Game Policy Data

The sampling frame comprised 21 video games included in ADL’s 2019[15] and 2020[16] “Free to Play? Hate, Harassment and Positive Social Experience in Online Games” surveys, as well as the 2021 “Hate Is No Game: Harassment and Positive Social Experiences in Online Games” survey.[17] Due to time constraints, a purposive sampling[18] technique was used to select a subset of games for analysis. With an emphasis on balance, 12 games representing a variety of genres (8) and game companies (9) were selected for the sample. Previous survey results were also taken into consideration during this process. Several games that ranked in the top five for in-game harassment or for positive social experiences in the last three surveys were included in the sample, particularly titles that ranked in the top five more than once.

Research Sample: Game, Company, and Genre Representation

Interview Data

Over six months, purposive sampling was used to select five participants. Purposive sampling was used because of time constraints and the necessity of gathering participants who had expertise regarding trust and safety and content moderation, especially in online games. Participants were also chosen based on their years of experience; all five participants have worked in trust and safety in games for at least five years.

Interview Sample: Name, Occupation, and Work Experience

Data Collection

Game Policy Data

Data was collected in January 2022. All data were obtained from publicly available digital sources such as official game and game company websites, in-game content, and ADL.org. Only data from 2019-2021 were collected.

Data collected included the following:

- Policy Guidelines

- Codes of Conduct

- Community Standards

- Terms of Use/Terms of Service

- In-game content (e.g., policy notifications, reporting interfaces, etc.)

- Development updates and metrics

- ADL reports

A complete list of sources may be found in the endnotes of this report.

Interview Data

Interviews were conducted over Zoom. Each participant read and signed a consent form. They agreed to be interviewed and have their views shared in this report. Each interview was one hour long. After each interview, the participant was debriefed and given further contact information from the research team.

Data Analysis

The game policy data and interview data were both analyzed qualitatively, using thematic analysis to identify key topics and compare them. Categories for analysis were drawn from ADL’s previous work published in conjunction with Fair Play Alliance, “Disruption and Harms in Online Gaming Framework,”[20] which identified types of disruptive behaviors in games.

The game industry has little transparency about how it measures disruptive behavior and harmful conduct. In lieu of categories from the industry, ADL, in collaboration with the Fair Play Alliance, created a framework to analyze game policies. This framework furnished the terminology used throughout this report as well as the categories used to analyze the games policies. This framework was explicitly designed to create a shared lexicon for those who study games.

ADL staff analyzed both policy documents and interview transcripts using MAXQDA 2022, a qualitative and mixed-methods analysis software. ADL evaluated each game’s policy to see how well it aligned with each category, such as banning hate or harassment. We also analyzed each game’s policies for clarity in rules. The interviews were also coded, though not using the provided categories. The interviews were coded based on patterns and themes that emerged based on questions pertaining to difficulties working in the trust and safety space and different strategies used to combat player toxicity. These findings were then used to identify themes and trends together with the games’ policies.

Donor Acknowledgments

The Robert Belfer Family

Craig Newmark Philanthropies

Crown Family Philanthropies

The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation

Righteous Persons Foundation

Walter and Elise Haas Fund

Modulate

The Tepper Foundation