Related Press Release

Fight Antisemitism

Explore resources and ADL's impact on the National Strategy to Counter Antisemitism.

Executive Summary

To better understand the current state of the campus climate for Jewish students, the ADL Center for Antisemitism Research (CAR), Hillel International, and College Pulse conducted a longitudinal survey of American college students before and after the Hamas terror attacks on October 7, 2023. The topline results, presented in this report, highlight concerning trends that underscore the urgent need to protect Jewish students on campus and foster an inclusive and safe educational environment for all.

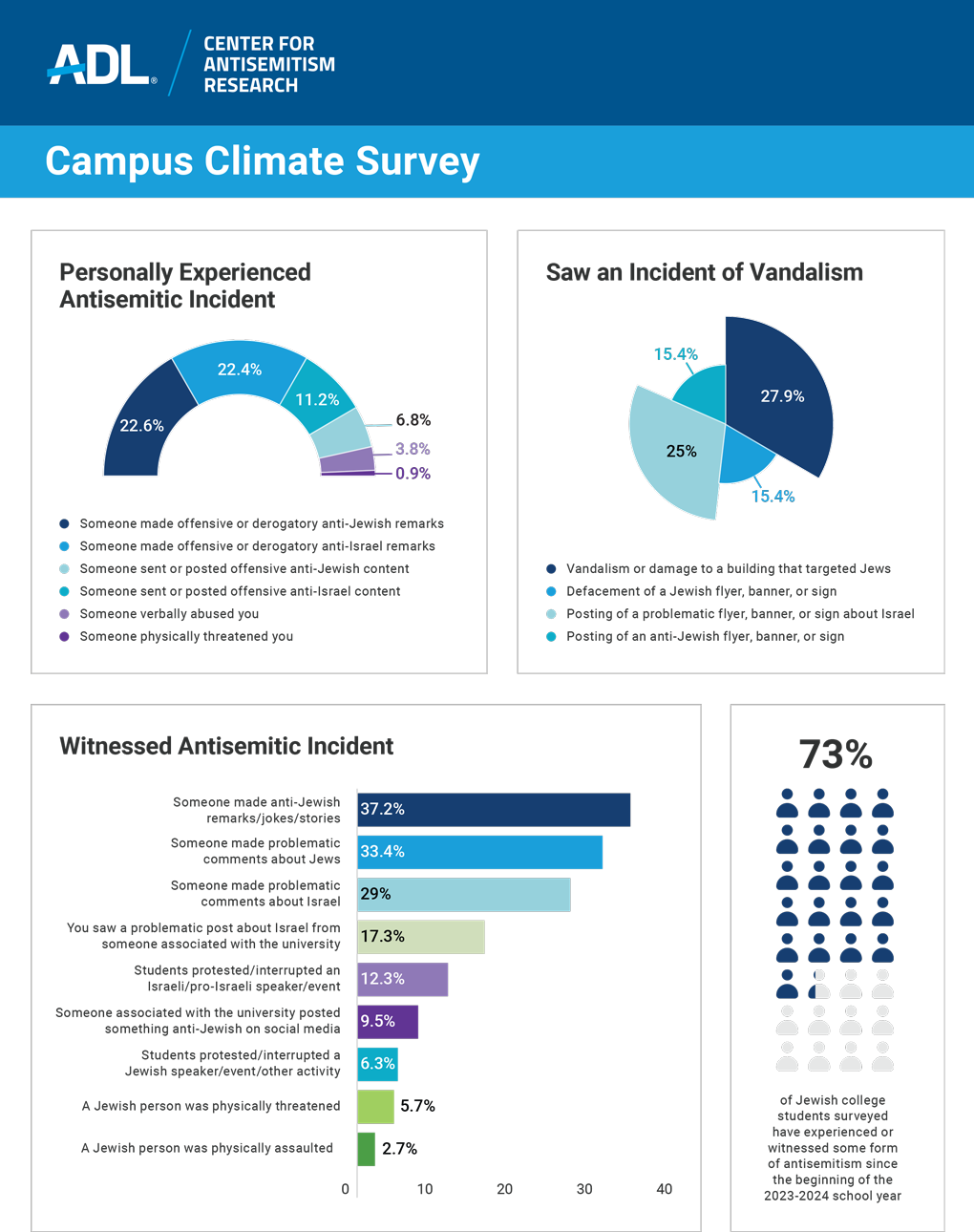

Jewish students are experiencing a wave of antisemitism, and non-Jewish students are much less likely to see it.

73% of Jewish college students surveyed have experienced or witnessed some form of antisemitism since the beginning of the 2023-2024 school year alone. By comparison, 43.9% of non-Jewish students reported the same during that period. Prior to this school year, 70% of Jewish college students experienced at least some form of antisemitism throughout their entire college experience.

Of the non-Jewish students erroneously assumed to be Jewish, nearly half (46%) stated that they had been targeted based on their assumed Jewishness.

26% of students assumed to be Jewish by others reported being on the receiving end of offensive anti-Jewish remarks, compared to 8.7% of those not assumed to be Jewish. Since 10/7, the proportion of non-Jewish students assumed to be Jewish has increased from 7.2% to 12.7%. Of this group, 29.5% reported being the targets of offensive anti-Jewish remarks.

Since October 7, the percentage of Jewish students who said they feel comfortable with others on campus knowing they are Jewish dropped by nearly half.

Since October 7th, students who have felt comfortable with others knowing they’re Jewish decreased significantly. 63.7% of Jewish students pre-October 7th felt “very” or “extremely” comfortable but now only 38.6% feel the same.

A majority of all students — Jewish and non-Jewish — feel like their campus administration has not done enough to address anti-Jewish prejudice at their universities, with 70 percent of students saying their university should do more to address the issue.

When asked who should do more to address the issue, most students (48.2% of Jewish students and 38.5% of non-Jewish students) placed the onus on campus administrators.

More than a third of Jewish students said they felt uncomfortable speaking about their views of Israel, and roughly the same proportion said they feel uncomfortable speaking out against antisemitism.

Nearly a third (31.9%) of Jewish students indicated that they have felt unable to speak out about campus antisemitism, while only 17.6% of non-Jewish students felt the same. 29.8% of Jewish students said that they would be uncomfortable with others on campus knowing about their views of Israel, compared to only 13.9% of non-Jewish students. After 10/7, these numbers increased to 38.3% and 18.9%, respectively.

A plurality of Jewish students do not feel physically safe on campus.

Prior to 10/7, two-thirds (66.6%) of Jewish students said they felt “very” or “extremely” physically safe on campus, compared to less than half (45.5%) post-10/7. Feelings of emotional safety among Jewish students changed even more dramatically – two-thirds (65.8%) of Jewish students said they felt “very” or “extremely” emotionally safe before 10/7, which fell to a third (32.5%) after 10/7.

Not knowing what to do and concern about potential backlash prevents students from reporting anti-Jewish incidents on campus, but even more so for Jewish students.

Of the 55% of Jewish students who reported doing nothing in response to an antisemitic incident, a large proportion reported fear of backlash as their reason for not responding. Of the Jewish students who had been the target of problematic anti-Jewish comments, for example, 14.8% said they did not respond due to fear that the perpetrator would target them again.

While a majority of university students have undergone DEI training, only 18% of those students have received any training about antisemitism.

55.8% of students surveyed said they had previously completed DEI training, but only 18.1% of those who had indicated previous DEI training said that they had completed any training specific to anti-Jewish prejudice. Though DEI programs have become increasingly common on campus, such programs remain limited in scope.

Campus Climate Survey

Introduction

ADL has long advocated for a more inclusive campus environment for America’s Jewish college students. This advocacy has taken on a renewed sense of urgency in the aftermath of the Hamas terror attacks against Israel on October 7, 2023, as anti-Israel protests employing inflammatory antisemitic rhetoric have swept university campuses across the nation and threats against Jewish students have increased in both number and severity.

Starting in August 2023, the ADL Center for Antisemitism Research (CAR), in partnership with Hillel International and facilitated by College Pulse, fielded a nationally representative survey of over 3,084 American college students, of which 527 were Jewish, from 689 campuses nationwide to gauge the climate for Jewish students across U.S. campuses. To ensure representation across different types of college experiences, students from both two- and four-year and public and private institutions with varying undergraduate enrollment numbers were surveyed. The survey asked an array of questions to measure student perceptions of whether, and to what extent, antisemitism is a problem on their campus, experiences with and responses to antisemitic incidents on campus, and their comfort level with other students knowing about their Jewishness or views of Israel. Students were also asked their opinions about whether and how well their campus administration had addressed the problem of anti-Jewish prejudice on campus.

In response to the alarming increase in antisemitism on college campuses in the aftermath of the 10/7 terror attacks, researchers paused data collection and re-fielded an additional survey with the same respondents in November 2023 to determine whether and how campus climate has changed since students were first surveyed at the start of the academic year. The post-10/7 survey asked many of the same questions to track change over time, with a particular focus on identifying whether there have been increases in antisemitic incidents based on real or perceived Jewishness or support for Israel and if students feel less safe on campus and less comfortable with others knowing about their Jewish identity or views of Israel. The survey also asked students whether they have experienced any adverse academic, social, or other consequences as a direct result of 10/7 and its aftermath, as well as their opinions about their university’s response to the Hamas attacks on Israel and the resulting conflict.

The results were sobering. Even prior to Hamas’s horrific terror attacks on Israel on 10/7 and the subsequent escalation of the conflict between Israel and Hamas, a substantial number of students—both Jewish and non-Jewish—were ambivalent about whether their campus is welcoming and supportive of Jewish students. At the same time, Jewish and non-Jewish students differed in their perception of whether campus antisemitism is a serious problem: while more than two in five Jewish students prior to 10/7 said that it was at least “somewhat” of a problem, only one in four non-Jewish students indicated the same.

Though college campuses have long been considered bastions of free expression, students consistently expressed discomfort with both speaking out about campus antisemitism and with expressing their views of Israel. This discomfort is especially high among Jewish students, and there has been a sharp increase in the number of Jewish students saying they feel the need to hide their Jewish identity from others on campus.

The data presented in this report support the reported rise in and effect of campus antisemitism post-10/7. The findings are also emblematic of an issue that has been festering on college campuses for much longer. Universities across the country would do well to heed these results and devise meaningful solutions to ensure that all students, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, are given an equal opportunity to maximize their college education and experience.

Antisemitic Incidents on Campus

Despite widespread discussion of antisemitic incidents on university campuses, we do not know the full extent, nature and impact of incidents because of underreporting. To address this gap, the survey asked nationally representative samples of Jewish and non-Jewish students a wide range of questions to track the following since they began as students:

- Incidents of antisemitic vandalism on campus;

- Antisemitic incidents that the student has personally experienced; and

- Antisemitic incidents that the student witnessed.

Of the nearly 700 college campuses surveyed, students from nearly half (46%) of these schools reported at least one antisemitic incident that they had either personally experienced, witnessed, or that constituted an act of antisemitic vandalism on campus. Incidents ranged in severity, from seeing the posting of a problematic flyer to instances of physical assault.

73% of Jewish students have experienced some form of antisemitism on college campuses just since the start of the 2023-2024 school year.

Prior to October 7th, 2023, slightly more than two in five (43.5%) Jewish students indicated they had been personally targeted by antisemitic incidents on campus at any point in their college career, and even more (63.4%) indicated that they had witnessed at least one incident during that same time. Specific incidents within each category ranged from observing antisemitic graffiti or flyers on campus, to witnessing problematic online comments about Jews or Israel, to being physically threatened or assaulted. A full breakdown and more detailed description of incidents by type can be found in the appendix.

It is important to clarify that pre- and post-10/7 incident data should not be considered an “apples-to-apples" comparison. The post-10/7 survey asked about student experience NOT in the entirety of their college experience (as was asked in the pre-10/7 survey) but ONLY since the 2023-2024 school year had started. Of the 1,218 respondents who appeared in both waves 1 and 2, 63.7% of Jewish students had experienced vandalism, 76.2% had witnessed antisemitism, and 40% had personally experienced antisemitism in just the weeks since the start of this academic year. Most of these students had experienced antisemitism on campus before, but 32.2% (n=216) first became victims of campus antisemitism in recent weeks.

Figure 1 below visualizes this stark increase: since this academic year began, the average monthly rate of antisemitic incidents witnessed by Jewish students has increased twenty-two-fold from that prior to this academic school year. The monthly rate of observing antisemitic vandalism for Jewish students increased by roughly twenty-one times, while the rate of experiencing antisemitic incidents increased 16.25 times.

Figure 1

Non-Jews

The extent of antisemitism is so significant that many non-Jews also have reported experiencing antisemitism. Roughly one in three (33%) non-Jewish students said they had seen, witnessed, or experienced an antisemitic incident on campus.

Figure 2 below shows the scale of this difference, with incidents witnessed increasing by nearly twenty-three times, observed antisemitic vandalism twenty times more, and experienced antisemitism 12.5 times more.

Figure 2

In addition to asking students whether they identify as Jewish in any way, the survey also asked whether anyone else had previously assumed that they were Jewish regardless of their actual background. Roughly 16% of those surveyed prior to October 7 answered affirmatively, with more than half indicating that they were assumed to be Jewish due to stereotyping based on physical features. 36% (n=183) of those assumed to be Jewish were not actually Jewish. Slightly less than one in five (18.8%) non-Jewish students reported having personally experienced an antisemitic incident. Of the non-Jewish students erroneously assumed to be Jewish, nearly half (47%) stated that they had been targeted based on their assumed Jewishness.

Not knowing what to do and concern about potential backlash prevents students from reporting anti-Jewish incidents on campus.

Students who reported having witnessed or experienced an antisemitic incident on campus were asked how they responded to the incident, with options including direct intervention in the situation, checking in with others impacted by the behavior, confronting the individual engaging in the behavior, seeking help from someone else, reporting or expressing concern about the incident or person to school administrators, or doing nothing.

Though responses by Jewish and non-Jewish students differed substantially, the most common response by far for both groups was doing nothing (55% and 30.9%, respectively). Of those who said that they did nothing, the most common reason across incident types for both Jews and non-Jews was that they "weren’t sure what to do.” For example, half of Jewish students who reported having witnessed a Jewish person being physically threatened gave this as their primary reason for not responding to the incident, while slightly less than half (44.4%) of non-Jewish students said the same.

Despite not knowing what to do being the most indicated reason for not doing anything in response to antisemitic incidents, there were some notable differences between Jewish and non-Jewish students. Chief among these differences is that a fear of backlash—including a fear of being targeted by the perpetrator and fear of negative academic, social, or professional repercussions—seemed to discourage Jewish students from responding to the incident more than for non-Jewish students. In the case of incidents involving problematic comments about Jews, 14.8% of Jewish students who experienced this incident said they did nothing due to fear that the person who did it would target them, compared to 8.5% of non-Jewish students. These trends held for incidents involving problematic comments about Israel, with 21.7% of Jewish students citing a fear of negative academic or social consequences as the reason for doing nothing versus 13% of non-Jewish students.

More in-depth analysis of the data revealed a strong statistical relationship between those who perceive their campuses to be less welcoming to Jews and the likelihood of experiencing but not reporting an incident. Even when controlling for individual-level variables such as age, gender, and political ideology, those students who perceived a more anti-Jewish campus environment were five times more likely to not respond to antisemitic incidents at all.

Fear about future antisemitic incidents

Fear about the potential for future antisemitic incidents on campus further underscores the challenges that antisemitism poses for all students on university campuses. Even before the 10/7 terror attacks, for example, one in four college students said that they thought it was at least somewhat likely that they would personally experience a future antisemitic incident, though this anxiety was significantly more pronounced among Jewish than non-Jewish students (42.3% versus 21.9%).

And when asked how likely they thought it was that they would witness an antisemitic incident on campus, 22% of all students said it was at least somewhat likely. Again, Jewish students were significantly more likely than non-Jewish students to fear that they would witness an antisemitic incident on campus in the future. It is noteworthy that of those non-Jewish students incorrectly assumed to be Jewish, anxiety around potential future antisemitic targeting was substantially higher than for those who had not been perceived to be Jewish: roughly one in three of this subgroup indicated that they thought it at least somewhat likely that they would personally experience or witness an antisemitic event in the future (32.8 and 31.8%, respectively).

Consequences of Campus Antisemitism

Students who experienced antisemitism on campus reported consequences ranging from difficulty focusing on academic work to considering transferring schools. Victims of antisemitic incidents on campus were also more likely to report feeling disconnected from their campus community and were less inclined to believe that campus officials take their well-being seriously.

Prior to 10/7, two-thirds (66.6%) of Jewish students said they felt “very” or “extremely” physically safe on campus, compared to less than half (45.5%) post-10/7. Feelings of emotional safety among Jewish students changed even more dramatically – two-thirds (65.8%) of Jewish students said they felt “very” or “extremely” emotionally safe before 10/7, which fell to a third (32.5%) after 10/7. When asked after 10/7 how physically and emotionally safe they felt on campus, Jewish students were substantially more likely to report feeling unsafe relative to the previous survey wave, regardless of whether they themselves had witnessed or experienced campus antisemitism.

This decrease in feelings of safety was even more pronounced for those students who reported witnessing or experiencing an incident of antisemitism on campus. Regression analysis across both survey waves showed a strong statistical relationship between antisemitic victimization and decreased feelings of physical and emotional safety on campus. Even when controlling for important individual-level demographic variables such as race, gender, and political ideology, witnessing or experiencing even one incident on campus was strongly associated with decreased feelings of safety on campus.

Figure 3

Figure 4

The consequences of antisemitic victimization on campus were widespread for both Jewish and non-Jewish students. Jewish and non-Jewish students alike reported suffering serious negative effects as a result of experiencing/witnessing incidents, highlighting the damaging effects of campus antisemitism on overall health and the social, academic, and professional lives of student victims. Though the results make clear that campus antisemitism is not only a Jewish issue, they also indicate a culture of internalized victimization and repeat trauma for Jewish students. When asked whether they experienced any consequences or negative experiences because of an antisemitic experience, the most frequent response among Jewish students was that they felt a need to avoid the person or people who perpetrated the incident. For example, the most frequently cited antisemitic experience for both Jews and non-Jews was being targeted by anti-Jewish comments, jokes, or stories by another person on campus. Of the Jewish students who reported experiencing this, a majority (60.6%) said that they had felt the need to avoid the person in the aftermath of the incident. And although Jewish students certainly reported other adverse effects due to their victimization, non-Jewish students were in some cases more likely to indicate that they experienced things such as difficulty keeping up with academic work or withdrawing from classes and limiting interactions with friends. For example, while 42.8% and 18.6% of non-Jews who were targeted by antisemitic speech or slurs reported that their academic work suffered or that they had difficulty going to work, 22.1% and 8.7% of Jewish students indicated the same.

When paired with high rates of nonreporting to campus officials, the similarly high rate of Jewish students indicating avoidance as their primary response to antisemitic victimization points to an insidious problem of Jewish students becoming inured to campus antisemitism through repeat victimization. Indeed, the second most reported effect of victimization among Jewish students across incident types is feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, a common indicator of negative mental health effects stemming from victimization. These findings suggest that Jewish college students have adopted a strategy of avoidance and silence in response to repeat victimization. This phenomenon is all too familiar to other historically marginalized groups when institutions fail to provide adequate protection or consistent mechanisms for redressing issues stemming from identity-based victimization.

Perceptions of Anti-Jewish Prejudice on Campus

More than two in five Jewish students think campus antisemitism is a problem

42.5% of Jewish students at least somewhat agreed that anti-Jewish prejudice is a serious problem on their campus. Over a quarter (27.2%) of non-Jewish students felt the same.

In recognition of the prominence of political activity on college campuses, students were asked whether they are concerned about anti-Jewish prejudice on campus from either moderates, progressives/those on the left, and conservatives/those on the right of the political spectrum. Both Jewish and non-Jewish students expressed concern, especially when it came to anti-Jewish prejudice from the right and the left (34.6% and 21.4%, respectively). However, there were significant differences between Jewish and non-Jewish students, especially when it came to the level of their concern. More than half (53.3%) of Jewish students who indicated general concern said they were “very” or “extremely” concerned about anti-Jewish prejudice from the political right, compared to 39.3% of non-Jewish students who indicated the same. More than a third (37.5%) of Jewish students who expressed concern with anti-Jewish prejudice from the political left on campus said they were “very” or “extremely” concerned, while 18% of non-Jewish students said the same.

Concern about anti-Jewish prejudice from various political groups on campus changed after 10/7, especially among Jewish students. While concern about anti-Jewish prejudice from political moderates and conservatives declined slightly for both Jewish and non-Jewish students, a slight increase in concern about the same from the political left increased. This slight increase is especially revealing when considered alongside the substantial drop in concern about anti-Jewish prejudice from political conservatives: among Jewish students, 29.3% indicated concern relative to 54.8% prior to 10/7. Concern about liberal prejudice among Jews remained roughly the same among Jews (44 to 44.2%) and increased slightly more among non-Jews (16.7% to 18.2%).

Jewish students’ views of their campus as welcoming declined significantly since 10/7

Before 10/7, roughly the same percentage (around two-thirds) of Jewish and non-Jewish students felt their school was very or extremely welcoming and supportive of Jewish students. Perceptions of universities being welcoming and supportive of Jewish students decreased for both Jewish and non-Jewish students after 10/7, but the decline is especially pronounced among Jewish students. While the proportion of non-Jewish students who thought that their university is “very” or “extremely” welcoming and supportive of Jewish students declined ten points pre- and post-10/7 (68% to 58%), there was a twenty-point decline among Jewish students (64% to 44%).

Figure 5

Self-Censorship of Jewish Students

Jewish students expressed high levels of discomfort with other students knowing they are Jewish

A worrying number of Jewish students reported feeling uncomfortable with other students knowing that they are Jewish. Prior to 10/7, 23.1% of Jewish students said they had felt a need to hide their identity versus 36.5% post-10/7.

Further, a substantial proportion of students said that they had felt like they could not speak out about antisemitism on their campuses. Roughly 20% of all college students said they had ever felt they could not speak about the issue, but the difference in responses between Jewish and non-Jewish students highlights a worrying trend of self-censorship among Jewish students. While 17.6% of non-Jewish students said they had felt unable to speak up, nearly a third (31.9%) of Jewish students said the same.

Since October 7th, students who have felt comfortable with others knowing they’re Jewish decreased significantly. 63.7% of Jewish students pre-October 7th felt “very” or “extremely” comfortable but now only 38.6% feel the same.

Figure 6

50% of students would be uncomfortable with others knowing about their views of Israel

Even prior to the 10/7 attacks, anti-Israel rhetoric and activity on college campuses had a chilling effect on free expression. When asked how comfortable they would be if others on campus knew about their views on Israel, nearly half of all students said they would feel not at all or only a little or somewhat comfortable. The difference in responses to this question between Jewish and non-Jewish students further points to a perceived need among Jewish students to self-censor when it comes to their views: nearly a third (29.8%) of Jewish students said they would be uncomfortable with others on campus knowing their views on Israel, compared to 13.9% of non-Jewish students. Conversely, only a fifth (20.9%) of Jewish students said they would be extremely comfortable versus more than half (54%) of non-Jewish students saying the same. Regardless of whether they were Jewish or non-Jewish, most students who expressed discomfort said they were uncomfortable expressing their views because they are not comfortable discussing Israel in large groups (34.3%) or because they were concerned what others would think of them (23%).

Importantly, the percentage of students comfortable with sharing their views on Israel has dropped since 10/7 as well but not as dramatically, from 30.3% to 22.4%.

Figure 7

Israel continues to be a uniquely contentious topic on college campuses. Indeed, when asked if they thought that disrupting a pro-Israel event was acceptable, 85.8% of respondents said it was unacceptable, while only 9.1% said it was acceptable. However, 4.7% thought it was acceptable to disrupt a pro-Palestinian event, 3.6% thought it was acceptable to disrupt a Pro-Russian government speaker, and 6.2% thought it was acceptable to disrupt a speaker from the Chinese government. While disrupting speakers was broadly unpopular, support for disrupting pro-Israel speakers was statistically significantly greater than the others examined.

One of the clear consequences of an unwelcoming campus environment for Jewish students is a dampening effect on involvement in campus life. Jewish students were asked if they had experienced several different scenarios on campus due to their Jewishness or due to their perceived support of Israel as a Jew, and their responses were telling. For example, nearly one out of every four (23.1%) Jewish students said that they had felt compelled to hide their Jewish identity – whether by abstaining from wearing visibly Jewish apparel or by refraining from mentioning that they were Jewish – from others on campus. More than one in three (34.2%) said that they had been assumed to hold particular views about Israel and Israeli policy because they were Jewish, and more than one in four (27.5%) said that they had been tokenized as a representative of all Jews. In addition to feeling compelled to hide or downplay their Jewish identity, many Jewish students said that they had felt unwelcome in various places on campus due to their actual or perceived support of Israel as a Jew: 13.5% of Jewish students said they had felt unwelcome in a campus organization and 10.1% had felt unwelcome in a classroom for this reason.

Administration Responses to Campus Antisemitism

Prior to the 10/7 attacks, a significant majority of college students indicated dissatisfaction with the way their university addressed campus antisemitism. After 10/7, students remained dissatisfied with responses from universities to the current conflict between Israel and Hamas. Additionally, after 10/7, over one-third of non-Jewish students indicated that they were unaware of what their university’s response was. This result suggests that university responses are not only dissatisfactory and widely unpopular among students, but also limited in reach.

Most students think that their colleges must do more to combat campus antisemitism

When asked prior to 10/7 if they thought their university should be doing more to address anti-Jewish prejudice on campus, a striking 70% of college students answered affirmatively. When broken down by Jewish versus non-Jewish students, Jewish students were more likely (76.5%) than non-Jewish students (67.3%) to say that their university should be doing more, yet this difference is less remarkable than the high number of both Jewish and non-Jewish students who were dissatisfied with how their school handled antisemitism on their campuses.

A different version of this question was asked after the 10/7 attacks to gauge student satisfaction with their university’s response to the situation in Israel and Gaza.

Table 1

As seen in Table 1 above, satisfaction was low among all students, with only 32.4% of Jewish students and 30.8% of non-Jewish students expressing they were satisfied with their university’s response. Approximately half of Jewish students (52.1%) expressed dissatisfaction with their university’s response, more than double the percentage of non-Jewish students who expressed dissatisfaction (25.4%).

A large percentage of non-Jewish students (36.5%) reported being uncertain as to whether their university had issued a response. It is unclear from this data whether the university did not issue a response or did not widely publicize their response, but this figure is illuminating regardless. Non-Jewish students may have been less likely to attend to the university’s response. Regardless of the precise reason, over one in three non-Jewish students did not know whether or how their university was responding to the conflict.

Relative to their non-Jewish peers, Jewish students are more aware of their university’s responses, but are less satisfied with them. Across the board, students who thought their university’s response to campus antisemitism was insufficient were most likely to say that campus officials should be doing more to address the issue, followed closely by faculty and student government. Of Jewish students who expressed dissatisfaction with their university’s response to antisemitism pre-10/7, nearly half (48.2%) said that campus officials should better address the issue, compared to 38.5% of non-Jewish students. 47.8% of Jewish students and 35.8% of non-Jewish students indicated that faculty should take on more responsibility, while 46.9% of Jewish students and 37.4% of non-Jewish students thought that student government should play a larger role.

When asked the same question after 10/7, 68.2% of non-Jewish and 66.1% of Jewish students thought that campus officials/employees, faculty, and/or student government should be doing more in response.

Jewish students still contend that campus employees or officials and campus faculty should be doing more to address antisemitism, followed by student government. In contrast, non-Jewish students were more likely to think that student government should play a larger role, relative to campus personnel. The percentage of non-Jewish students expressing that student government should play a larger role has increased since 10/7.

Before 10/7, roughly 40% of Jewish students reported that they had previously expressed their concerns about anti-Jewish prejudice on campus to either campus officials, faculty, or other students. Of those who expressed concern about campus antisemitism to officials or to other students, however, only a quarter of students thought that their concerns had been taken “very” or “extremely” seriously. Those who expressed their concerns to faculty members were even less likely to be satisfied with their university’s response, with less than one in five saying that their concerns were taken very or extremely seriously.

More than three in four college students want DEI initiatives to include education about anti-Jewish prejudice

In recent years, many universities have made efforts to expand diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives in response to concerns about inequities for marginalized groups in the academy. With few exceptions, the exclusion of treatment of anti-Jewish prejudice in these initiatives has been conspicuous. More than half (55.8%) of students surveyed said they had previously completed DEI training, but only 18.1% of those who had indicated previous DEI training said that they had completed any training modules specific to anti-Jewish prejudice. This discrepancy suggests that, while DEI programs have become increasingly common on campus, such programs remain limited in scope.

Despite limited exposure to education about anti-Jewish prejudice in DEI initiatives, Jewish and non-Jewish students alike support expanding DEI programs to include such discussions.

Table 2: Should DEI cover anti-Jewish prejudice?

As Table 2 shows, both Jewish and non-Jewish students overwhelmingly support including discussions about anti-Jewish prejudice as a part of DEI programming, with 84% indicating at least some level of agreement. Nearly three-quarters of non-Jewish students similarly support discussing anti-Jewish prejudice in the context of DEI. Though Jewish students were slightly more likely to support anti-Jewish prejudice discussions in DEI, the topic is popular among all students.

Conclusion

It is difficult to overstate the concerning findings revealed by this study. Over the past few years, several research projects focusing on Jewish experiences on college campuses have pointed to a growing problem, including ADL’s 2021 survey of students from over 1,000 colleges nationwide that observed an increase in antisemitism on campus. Within the 2020-2021 academic year, nearly one-third of Jewish students personally experienced antisemitism, most commonly offensive comments or slurs online or in person. 31 percent of Jewish students witnessed antisemitic activity that was not directed at them, such as antisemitic symbols, logos, and posters.

We now know the problem has gotten far worse. Majorities of Jewish students at colleges are experiencing antisemitism during their years on campus, uncomfortable with their campus communities knowing that they’re Jewish, and a plurality are afraid of a backlash from those communities if they report an issue. Campus antisemitism has far-reaching implications, the scope of which extends beyond the context of current events.

This study demonstrates not just the impact of antisemitism on students but also the systemic failures of campus administration. We hope this study makes it clear that ignoring or gaslighting students experiencing antisemitism substantively contributes to an unsafe campus climate. The breadth of the problem requires a broad and comprehensive response, and addressing this scourge requires real action from campus organizations, faculty, campus administrations, residential life, and campus security.

Appendix

Methodology

The survey instrument used for this study built in part on that developed as part of ADL and Hillel International’s 2021 campus climate study. This survey, like the previous, was fielded by College Pulse, an online survey and analytics platform focused on American college students[1]. College Pulse’s proprietary panel includes more than 675,000 college students from more than 1500 institutions of higher education across all fifty states. Both waves of this survey employed an oversample of Jewish students, with 527 Jewish students responding in the first wave and 457 responding in the second.

The first wave of the survey was conducted in the summer of 2023 from July 26 to August 30, yielding a robust sample size of 3084 students. The second wave of the survey was fielded one month after the October 7 terror attacks, from November 6 through 10. Time constraints imposed by the need to collect unbiased and quality data necessitated a shorter fielding window, resulting in a sample size of 1606. Of these, roughly 70% of respondents (n=1218) had also responded to the first wave survey, including nearly half (n=261) of Jewish respondents from the first wave. The abridged instrument recycled key questions from the first wave survey that allowed for a longitudinal analysis of important issues, such as perceptions of and experiences with antisemitism on campus and opinion about university administration responses to anti-Jewish prejudice on campus.

Donor Acknowledgement

The work of the ADL Center for Antisemitism Research is made possible by the generous support of:

Anonymous

ADL Lewy Family Institute for Combating Antisemitism

The Crimson Lion/Lavine Family Foundation

David Berg Foundation

Lillian and Larry Goodman Foundation

Diane & Guilford Glazer Foundation

The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Foundation

Erwin Rautenberg Foundation

ADL gratefully acknowledges all of the individual, corporate and foundation supporters who make our work possible.